The Proposed Anti-Superstition Legislation: Facts & Myths

Published on

It is not what the man of science believes that distinguishes him, but how and why he believes it. His beliefs are tentative, not dogmatic; they are based on evidence, not on authority or intuition.

– Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy

The distinctive feature of science is its method of logical justification of theories based on evidence gathered via scientific methods and techniques. As science advances in a society, it is expected to usher in the ideals - scientific inquiry, rationality and critical thinking among the people. However, today one finds a society that receives accolades for its commendable achievements in science and technology; and at the same time, becoming increasingly superstitious. A disturbingly high number of superstitious practices that cause significant harm and exploitation of the masses, are being perpetuated and tolerated by the ‘civilized society’. Such harmful practices are not restricted to a particular religion, class, caste, creed, language, sex, place, profession, or any other man-made or natural attributes, but are pursued even by scientists and engineers etc who - as demanded by their professions - are expected to have a scientific outlook.

One may argue that to be superstitious or not, is a matter of private domain and it is not desirable to have state’s control on the matter. Such a stance however needs to be reevaluated in light of the immense exploitation that these occult practices cause to the masses, especially those belonging to the marginalized sections. These practices often become a tool in the hands of socially and economically powerful sections of the society to silence opposition and further their social positions and vested interests. Such practices are deeply entrenched in the hierarchical and oppressive social system and they continually pose threat to people’s lives, livelihoods and their dignity. Women, Dalits and children – especially those who have stood up against the discrimination that they encounter in their daily lives - often fall prey to such nefarious elements. Therefore, defending superstitious activities under the garb of individual choice, not only gives further leeway to those engaging in such harmful practices. It also makes the fight against such dangerous obscurantism difficult; difficult to the extent that people who garner strength to raise their voices against such blind beliefs are muted, as we witnessed in the brutal murders of rationalists Dr. Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare in Maharashtra and Prof. M. M. Kalburgi in Karnatka.

Figure 2: A photograph of two Devadasis taken in 1920s Chennai in India

Following the assassination of these rationalists, there has been a widespread outrage felt by academics, activists and the general public at the current state of affairs. This has further consolidated the demand for a strong anti-superstition legislation as has been a demand of these brave men for decades. As a result of the mounting pressure, within few months after the murder of Dr. Dabholkar, the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly passed The Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and other Inhuman, Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Act, 2013.

Legislative interventions have been employed even in the past to fight specific superstitious practices. For instance, there exist legislations such as The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, specific provisions in the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisement Act), 1954 and few state legislations which criminalize practices like witch hunting, Ajalu practice, Devadasi system etc.

Following this tradition and with the passing of the Maharashtra anti-superstition legislation, a cross-section of academics, writers, legal experts, progressive thinkers and scientists, came together in drafting The Karnataka Prevention of Superstitious Practices Bill 2013 (hereinafter ‘the Bill’). Even though this Bill has generated considerable interest and debate in the state ever since it was presented to the government, it has been shelved by the state government for the past two years.

Is the proposed bill against freedom of religion?

Despite there being legal precedents, there is immense suspicion and uneasiness in using such laws in the fight against superstitious practices. This suspicion has even thwarted any and all attempts at exploring the potentialities of law and has given a way to propaganda being unleashed against such attempts in a sustained manner.

This is because, adopting a legislation against superstitious practices is often seen as an attack on the freedom of religion and those fighting for such a law are portrayed to be offending religious beliefs. Rationalists and reformers have recently come under immense pressure with rampant misuse of Sections 295A and 298 of the Indian Penal Code. While Section 295A outlaws deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs, Section 298 criminalises uttering, words etc., with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person.

Though these sections were intended to promote communal harmony, they are being used by many to stifle opposition to the harmful practices that are being propagated in the name of religion and culture. It should be noted that freedom of speech guaranteed by the Constitution gives us the freedom of dissent, subject of course to reasonable restrictions provided therein. Social reform cannot take place without rational condemnation of such evil practices, and it was only through sustained criticism of reformers in the past that we were able to eradicate heinous and oppressive practices like Sati. Child Marriage

Figure 3: Wedding party, by Lady Ottoline Morrell

While our constitution guarantees right to freedom of religion to every citizen, this fundamental right is not absolute and - as the Constitution itself clearly states - is subject to public order, morality, health and the other provisions of Part III which enumerates other fundamental rights. Freedom of every religious denomi-nation to manage its own affairs in matters of religion is also subject to public order, morality and health. Significantly, Article 25(2)(b) of the Constitution expressly reserves the State’s power to make laws providing for social welfare and reform, even when it might interfere with a person’s fundamental right to freedom of religion. In no circumstances, this right can be extended to undertake harmful and exploitative practices. This was recognized by the Bombay High Court in 1862 itself, in Maharaja Libel case, wherein the judgment stated: ‘what is morally repugnant can never be religiously sanctioned’.

Contrary to the propaganda unleashed against the bill that, on its enactment, it will even infringe upon one’s choice to wear a veil ormangalsutra, the Bill actually goes on to define what superstitious practice it actually intends to criminalize.

As per the Bill, only those acts done by invoking a purported supernatural power, with the promise of curing a person (or group of persons) of disease or affliction or purporting to provide a benefit, or threatening them with adverse consequences, and thereby causing grave physical or mental harm to such person or group of persons, or resulting in their financial or any sexual exploitation or offending their human dignity will constitute a ‘superstitious practice’.

In addition to the acts that constitute a superstitious practice by virtue of this definition, there are certain specific superstitious practices such as aghori, siddubhakti, made snana, panktibheda etc., that the Bill criminalizes. In this context, it should be noted that even the Maharashtra legislation does not broadly define what constitutes a superstitious practice and merely penalizes certain specific superstitious practices enumerated in its schedule.

Can an anti-superstition law curb superstitious practices?

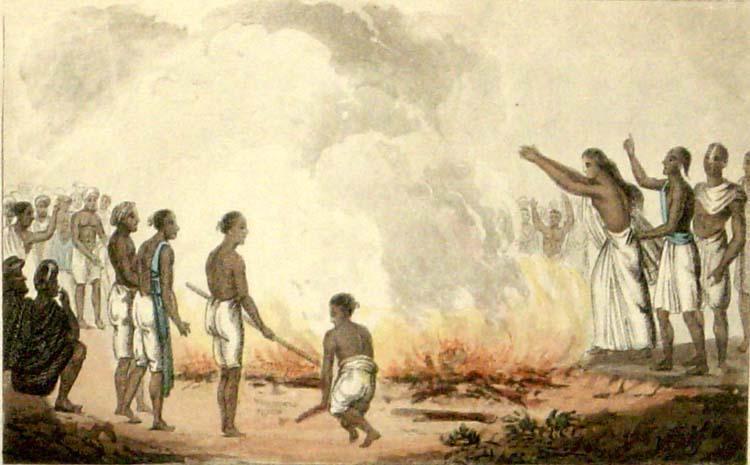

Figure 4: A Hindu widow burning herself with the corpse of her husband, 1820s

Alongside the objection that an anti-superstition legislation obstructs religious freedom, there is also a viewpoint that legislations cannot be of much help to save the society from such blind beliefs and regressive practices. This critisism points to a need for social and religious reform instead of a legislative approach. Similar arguments were raised even during the process of adopting legislation against social evils like Sati and child marriage.

However, history has shown that legislative interventions have had considerable effect in eradicating or at least marking a significant reduction of these practices. For example, the effect of the Maharashtra legislation, can be seen in the fact that 150 cases being registered [^toi20150821] under it, within a span of 18 months from the date of its enactment. This is no small number especially when we gauge it in the context of fiercely superstitious society in which such legislation has to operate.

Wherever legislations did fail, it has been mainly on account of ineffective implementation or a lack of awareness of the protection provided by them, among other factors. This is well demonstrated in the case of The Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995. The rule 6 of the Cable Television Network Rules, 1994, clearly states that no program should be carried in the cable service that, among others, ‘encourages superstition or blind belief’. Even though this act prescribes a punishment of imprisonment up to two years for a first time offender, this legislation is hardly enforced by the authorities, largely owing to a lack of awareness about the existence of such a legislation.

On the other hand, even well-known laws become ineffective because of the shockingly low punishments that are prescribed by them. For instance, the Jharkand state legislation against witch hunting provides a mere six month’s imprisonment for physical and mental torture meted out to a woman that has been “identified as a witch”. This punishment is in fact very low compared to equivalent general offences under Indian Penal Code for assault or grievous hurt. According to the Bill however, any person who promotes, propagates or performs a superstitious practice is liable for punishment with imprisonment for a term between one to five years or with fine between ten thousand to fifty thousand rupees, or both. Except in cases expressly mentioned under the Bill, offences are cognizable and non-bailable in nature.

Implementation of the bill

The bill conceives of a dual mechanism for its implementation, which includes “Karnataka Anti-Superstition Authority” and the district level Vigilance Committee on Superstitious Practices. These bodies can receive individual complaints from any person or take suo motu cognizance of violations of this legislation by any person or organization, and report them to the police for necessary action. The other duties entrusted upon them include: holding awareness generation campaigns; auditing primary and higher education curricula, to further the development of scientific temper and recommending appropriate corrective measures; facilitating research on the effects of superstitious practices etc. These details demonstrate that the current draft of the legislation realizes that mere penalizing of certain acts is insufficient to effectively eradicate superstitious practices.

Other provisions, such as the ones extending protection to victims as well as those fighting such practices, are indeed progressive. The bill explicitly states that having the consent of victim is not a valid defense and that the victims of any superstitious practices shall not be deemed guilty of committing or abetting the practice. This will allay the fears in the mind of victims and provide them the assurance to report such offences to the authorities.

In addition the Bill stipulates setting up of a Prevention of Superstitions Fund by the State Government that among other things, provides relief, compensation and rehabilitation to the victims of superstitious practices. This Fund is also to be used by the earlier mentioned statutory bodies to promote awareness and education on development of scientific temper and the need to prevent superstitious practices.

Conclusion

Despite well-thought out provisions, the draft Karnataka Prevention of Superstitious Practices Bill is being opposed today for all the wrong reasons, by those with vested interests who are vehemently obstructing an informed public debate on the proposed Bill. While it is not anyone’s argument that a legislation will change things overnight, such a legislation will undoubtedly be a powerful weapon in fighting occult practices and advancing scientific temperament and rationality in the society. After all, it is a constitutionally mandated fundamental duty of the citizens of India to promote scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform. An anti-superstition legislation can provide sufficient protection to those who take this duty seriously.

Image Credits

A photograph of two Devadasis taken in 1920s Chennai in India -- by Bhadani, released into the public domain

Wedding party, by Lady Ottoline Morrell -- by Lady Ottoline Morrell, released into the public domain

A Hindu widow burning herself with the corpse of her husband, 1820s -- by Frederic Shoberl, released into the public domain