Caste in India – Evolution & Manifestation – An Interview with Prof Anand Teltumbde

Published on

Figure 1: Prof. Anand Teltumbde

Professor Anand Teltumbde is a management professional, writer, civil rights activist and political analyst. He is the author of The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji Murders & India’s Hidden Apartheid and other books on Caste and Class in India. He is currently a faculty in the Vinod Gupta School of Management at IIT Kharagpur. CONCERN interviewed Prof. Teltumbde over email on Casteism in India.

Do you agree with an assessment that most institutes of higher education, particularly among the Science & Technology disciplines, have been apolitical? What is the reason for this?

It is not quite correct. In the late 1960s the radical politics firstly took roots in elite engineering colleges of the country. The then Regional Engineering Colleges (currently called NITs) had become the centers of radical student politics. Many naxalite leaders came from these colleges. Even IITs did not remain unaffected. It is not difficult to explain this phenomenon. Science and technology (S&T) students are relatively more sincere, focused, objective, and have prowess for rational thinking. They tend to look at the world around from the same analytical viewpoint as they do the physical world. The theories of Marxism with their scientific method and promise of change are more likely to appeal to them than to others.

However, on the other side there is a stronger lure of better career if they persist in their studies. The opportunity cost of radical politics rises with the risk associated with radical politics. The horrific repression the naxalite movement suffered in Bengal and then in other parts of the country generally created a scare wave that multiplied this cost. The rational thinking that impels them to radical politics also dissuade them away from it.

Later, after the advent of neoliberalism, things changed for worse. The collapse of Soviet block and reversal in China in intervening times weakened the appeal of Marxism. Neoliberalism subtly worked in, pulverizing society into discreet individuals who would be increasingly vulnerable with rising crisis engendered by its social Darwinist policies. There was euphoria in corporate world with the rise of new sectors of economy enabled by new technologies. The good students with S&T background were promised irrationally high salary packages. It thus increased the opportunity cost manifold with simultaneous risks of repression by the neoliberal state. It is therefore that the S&T campuses appear apolitical. As a matter of fact, not only the S&T campuses but almost all campuses have been depoliticized over the years. Campus politics is virtually decimated during the neoliberal era.

Actually, campuses of higher education institutions are not the factories to feed corporate mills with inert human resource tutored in various things to run the businesses as ongoing entities. They are supposed to equip students with critical faculties to make them discern right and wrong to shoulder the larger responsibility towards human society as citizens. This can only be accomplished through campus politics.

How has Caste evolved in modern India? Were the independence and the Mandal Commission landmarks in this process? Where from does the modern India start? I think we can reckon it from the establishment of British colonial rule in India. Momentous changes befell during the colonial rule in the context of castes. Capitalism came to India piggy-backing it. While purely from their own colonial logic, the British undertook massive infrastructure (roads, railways, ports, communication network, urbanization, etc.) and institution (police, justice system, taxation system, etc.) building, it hugely impacted the Hindu social order. Marx for instance saw at the time of introduction of railway network that it would lead to collapse of the decadent structures like castes. Many people lament that he was proved wrong but I think otherwise. The spread of capitalism did have debilitating impact on castes in as much as it killed associated ritual notions of castes among the communities that came in contact with capitalism. The dwija castes in urban centers that adopted capitalist (mercantile or industrial or both) entrepreneurship, found caste exclusion a hurdle in their business relationship and slowly adjusted to ignore them. It needs to be noted that castes emulate the advanced sections within; the latter determine the laws and valency of customs. While not all dwija castemen became capitalists, following their leaders, they also came to discard rigid ritual notions of castes. The colonial regime proved a veritable boon to the lower castes, particularly Dalits, which were one of the important pivots of the caste system. The entire articulation of Dalits and their movement could be attributed to the changes that happened during the colonial regime.

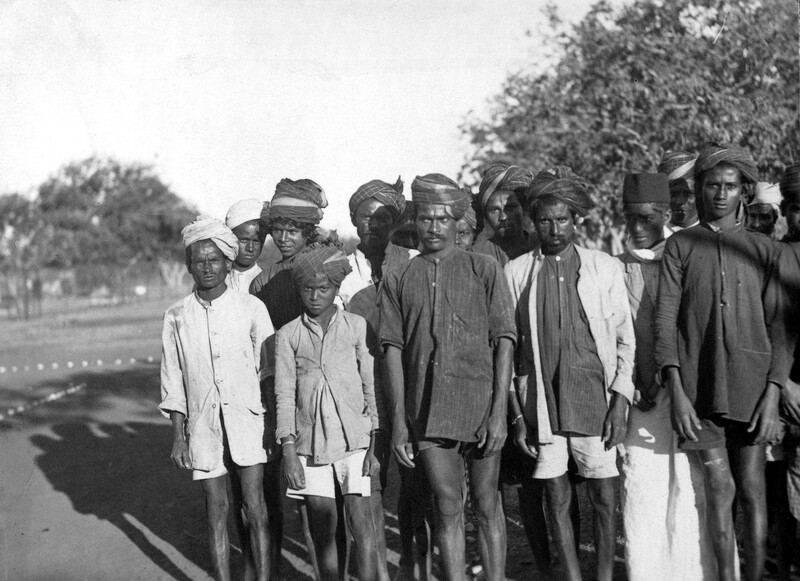

Figure 2: A school for untouchables near Bangalore (March 1935)

With the entry of the British in India, Dalits got opportunities to get into their employment as domestic servants, and military men. The latter proved vastly liberatory as it enabled them to realize their military prowess. They won many battles for British. Symbolically, the credit for the ultimate defeat of Peshwai at the battle of Bhima-Koregaon that established the British empire goes to the bravery of the Dalit soldiers. This helped them to discard the internalized notion of inferiority instilled by the Hindu social order of centuries and germinate the consciousness of human right. They also immensely benefitted from education customarily provided by the British to their armymen. For the civilian population, the Christian missionaries did the job. When the infrastructure projects began dotting the newly come up urban centers like Calcutta, Chennai, Mumbai, etc. Dalits benefitted immensely in exiting their bonded existence in villages. They accomplished significant economical progress to constitute a class of incipient middle class which could articulate liberation of the Dalits. Dr Ambedkar, himself could be seen as the product of this process.

While these changes took place in urban centers, the vast rural India remained largely unaffected. It would undergo change only after the transfer of power. The changes wrought during the post-1947 period, according to me, are unparalleled in the history of India. It overhauled entire configuration of the country. But these changes unfortunately were driven in negative direction with regard to casteism and communalism and their victims like Dalits and minorities.

The new ruling classes in the Congress Party feigning concern for people, worked for the interests of the incipient bourgeoisie whom they truly represented. The entire process of transfer of power including the partition of the country was worked in collusion with the British/American imperialism. The constitution making also was a part of this schema with its liberal façade that would permit near communist rule at the one end and at the other, total Fascism. Association of Babasaheb Ambedkar as its chief architect also was a feat of deceitful stratagem in this schema.

Figure 3: A banner outside the 2012 Republican National Convention in the USA depicts one of the quotes of Martin Luther King, Jr

The new ruling classes created an impression of socialist leaning but actually drove everything to serve the capitalist interests. They announced five year plan, thereby projecting emulation of Soviet Russia, but actually borrowed its content from the Bombay Plan prepared by eight of the then prominent capitalists in the country, which was earlier publicly disapproved by Nehru. They undertook land reforms, seemingly in keeping with the promises of the freedom struggle, but implemented them in such a way as to create a class of rich farmers in rural India which would be an ally of the central ruling party as well as feeding the growing hunger of capitalist for raw materials. The slogans like ‘land to the tillers’ created an impression of pro-people policies but they were actually needed to maintain political stability for the prosperity of capitalists. The actual tillers among Dalits did not get land with an alibi that they did not figure as tenants in records and lands were given to the shudra caste famers. The Green Revolution, a capitalist strategy to enhance agricultural productivity followed close on the hills of the half baked land reforms, enriching the newly created class of farmers from among the shudra caste band. History shows that the class emerges dominant and constitutes a state. It was for the first time that the state came first and created its congenial class.

Figure 4: Inauguration ceremony of Kilvenmani martyr's memorial in Nagapattinam (2014)

The upper caste landlords having left villages, the baton of Brahmanism came into the hands of these rich farmers. The Green Revolution catalysed the spread of capitalist relations through the advent of various markets for input, output, implement, service, credit, etc. leading to collapse of the traditional jajmani (or such other) relations of interdependence. Moreover, the change in caste configuration of the village would be further detrimental to Dalits because unlike the erstwhile upper castes lords of the village the newly dominant caste was most populous. The Dalits were reduced to be pure rural proletariat utterly dependent on the farm wages from the rich farmers. The resultant class contradiction between the Dalit farm labourers and rich farmers began manifesting through the familiar fault-lines of caste into what I call the new genre of caste atrocities. They were the product of growing cultural consciousness among Dalits and the material oppression they faced in newly configured village. As we know, it first erupted in Kilvenmani in Tamilnadu, where 44 women and children of Dalit farm labourers were burnt alive by the landlords and their henchmen in 1968.

These atrocities would soon spread all over and assume menacing proportion. Caste atrocities, which could be taken as proxy for casteism, did not show any definitive trend until 1980s, but after 1990, it clearly depicts a secular rising trend. The National Crime Research Bureau (NCRB) shows their rise from 33507 in 2001 to 47,064 in 2014. The rising agrarian crisis in rural India due to neoliberal policies and growing cultural assertion of Dalits has been the major cause for this phenomenon.

The newly created class of rich farmers indeed worked as an ally of the Congress Party. They began investing their growing surplus into petty businesses like cold storages, processing units like dal mill, rice mill, oil mill; transport, contracting, etc. With growing enrichment they developed their own political ambition and began hard bargaining the share of political power and economic concessions from the ruling party. Soon, it manifested in emergence of regional parties threatening the monopoly of the Congress. With increasing competition, the importance of the vote blocks in the prevailing first-past-the-post (FPTP) type of election system went on increasing. Since such blocks existed in the form of castes and communities, in turn, the political parties began wooing them. Out of these castes, Dalits accounting for some 16 - 17 % votes were the most vulnerable and hence relatively cheaply available for manipulation. This process of wooing Dalits by the political parties added to the existing grudge in the larger society. One can distinctly observe the co-optation of Dalit leaders, decimation of independent Dalit politics, building up of ‘Ambedkar icon’ as the manipulative tool and aggravating their vulnerability by unleashing atrocities happening simultaneously.

This process further led to consolidation of the non-Dalit castes. The process of collapse of dwija castes through decimation of ritual aspects of castes extended to the upper class layer of the shudra castes as they increasingly involved in political and business transactions. With the caste ties, the shudra bandwagon also in course got hitched to the diwja bandwagon, thereby creating a virtual non-Dalit block. The Mandal Commission also could be seen as the manifestation of growing empowerment of the backward (shudra) castes. This process transformed castes into a simple class like configuration of Dalits and non-Dalits.

Alongside, one must note that the intrigues around castes played out in the making of the Constitution. The Constituent Assembly had unanimously decided to outlaw untouchability with the cheers of Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai but skilfully preserved castes with a convoluted alibi that it wanted to provide for social justice for the lower castes. Everybody knew that all upper caste reformers, best represented by Gandhi, were embarrassed by the inhuman custom of untouchability and wanted it to go but none spoke unequivocally about annihilation of castes. Therefore, there was nothing surprising about them outlawing untouchability. However, untouchability was an integral manifestation of castes and could never disappear as long as castes survived. As such nothing really happened by outlawing untouchability. It is being rampantly practiced as the surveys after survey right from 1950s to just the previous day, NCAER (National Council of Applied Economic Research) report, reveals. Castes instead of being annihilated were given a new lease of life in the Constitution. As is known the alibi was to provide for the reservations.

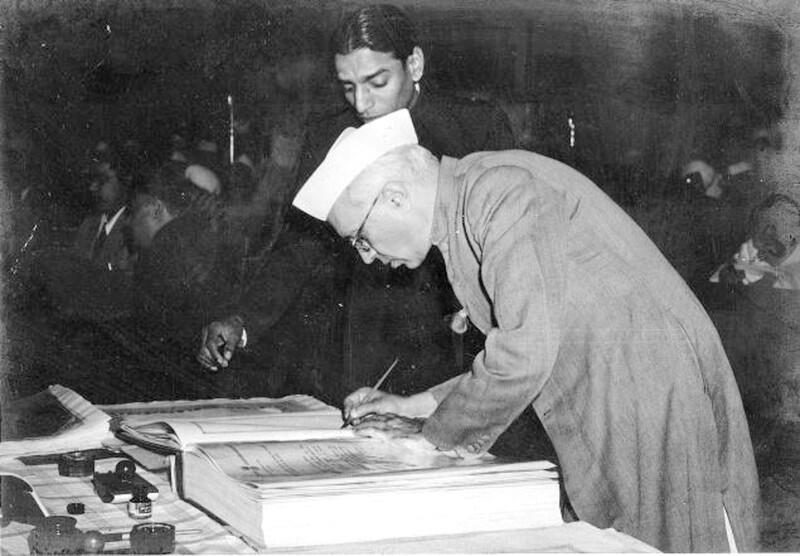

Figure 5: Prime Minister Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru signing a copy of the Indian Constitution (1950)

When the colonial rulers instituted reservation policy in favour of Dalits, it, although not described in so many words, had a basic feature of being an exceptional policy measure for exceptional people. When the transfer of power took place, could this policy be discontinued? Although the theoretical answer to this question could be affirmative, none having political acumen could say so. Politically, it would have been the riskiest folly on the part of the rulers. If so, the reservations were not to be freshly instituted; they were principally stabilized in the colonial times. More importantly, the colonial powers, despite their zest for marshaling everything to serve their divide and rule strategy, had created an administrative category of ‘scheduled caste’ to supersede the religion-ordained caste of the Untouchables. There was a clear opportunity for the new ruling classes, who took over from the British, to outlaw castes too. But they hoodwinked people outlawing only untouchability. They had not stopped at that; they diluted it by extending it to potentially all and sundry. They created a separate schedule for the tribals to have ditto provisions of the scheduled castes. Notwithstanding the lack of foolproof criteria to identify people in this schedule for tribes, they could have been merged into the existing schedule (suitably renaming it) and thereby diluted the caste stigma associated with the schedule for Dalits (because the tribals did not have caste). They haven’t even stopped at that. They would create a vague provision that the state would identify the ‘backward classes’ (read castes) so as to extend similar provisions in future. It verily amounted to constructing a can of caste worms the lid of which could be opened at an opportune time in future as the Prime Minister VP Singh did in 1990. The entire schema about castes being kept alive comes out clear when we see similar scheming around religion, the other weapon to divide people.

Figure 6: VP Singh, Prime Minister of India (1990)

The Constitution scrupulously avoided the term ‘secular’ that could create a separating wall between religion and politics with an alibi to have space for the state to carry out religion-related reforms. The only reform that one could imagine was in the form of passing the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 in the wake of burning of Roop Kanwar on her husband’s pyre. It is important to understand these matters because they directly cross the emancipation agenda of Dalits. The answer to the second part of your question is thus yes.

The post-independence ruling classes had overtaken the colonial masters in treachery. Castes, instead of an opportunity to annihilate as explained, were given a new lease of life. They have used the colonial policy but mutilated it in such a way as to forge a powerful weapon out of it. The Mandal Commission was a part of this schema. It was, as I said, a can of caste worms. Its implementation led to re-castization of society. The reservations for Dalits and Adivasis were almost normalized but the Mandal reservations opened up the entire issue of reservations and brought the reservations of Dalits into question. It was a mix of age old prejudice against Dalits as ‘inferior’ people, accentuated by their cultural assertion, and the perceived favour of the state which grew as the electoral competition increased by the late 1960s. The reservation became an open ended policy which could be granted to any caste if it could prove to be ‘socially and educationally’ backward. The agitations of castes broke out everywhere demanding reservations as the OBCs or the Scheduled Tribes but never as the Scheduled caste, proving thereby the salience of castes. The political parties promoted it to garner votes in elections.}

How does Casteism differ in Urban & Rural spaces?

Caste has been a life - world of people which adapts to its surroundings like any organic life. The urban setting is not amenable to the kind of observance of castes as in remote villages where one confronts its crude forms. Largely, caste remains at the level of prejudice.

As stated above, the castes have been reduced to simple class like divide between Dalits and non-Dalits. Among non-Dalits it stays as cultural residue sans any ritual sense. But it is more pronounced at the classical kink in the caste continuum dividing Dalits and non-Dalits. Over the decades, Dalits have made significant progress, thanks to reservations. Although minuscule compared to their population, this class became visible in cities and towns.

Urban spaces are not immune to casteism

The operation of castes, however, presents a complex pattern. It is seen that the salience of castes is often associated with the material aspects. It depends upon options available. For example, in situation of supply constraints, Dalits are accepted as in the IT sector. They may, however, be marked down vis-à-vis their counterpart. The phenomenon is commonly seen in our elite institutions, where Dalit students are picked up readily but generally marked down vis-à-vis their non-Dalit counterpart. The explanatory variables to some extent are cultural attributes that the Dalit students do not reflect the class upbringing that the recruiters expect but the influence of caste also plays a part. There is a tacit association of inferiority with Dalits. These days the second and third generation Dalit students appear to perform as good as any other in admission tests. But it is commonly seen that in personal interviews they are never given good marks because of the bias that if they are given marks they deserved, they would come into open merit and deprive a general category seat. I have experienced this play of prejudice all through my career.

In organizations, particularly the public sector undertakings (PSUs) where Dalits land up for security reasons, a different kind of dynamics plays out. The PSUs are monitored for their compliance with the statutory provisions for the SCs/STs in terms of numbers. As anywhere, the discrimination is often associated with other secular factors. A Dalit employee who is more pliable is preferred and elevated as a demo-piece to demonstrate non-discriminatory treatment of Dalit employees. They are used as official representatives of their caste as required by the policy to validate actions of the management. It helps management to size up assertive Dalit employees. Since a favoured Dalit employee would be extra-beholden to his managers, it serves the interests of the latter even in manipulative practices.

It is simplistic therefore to talk about caste discrimination being only due to caste without reference to other factors. Caste may be understood as premium or discount over the base price. The Brahman gets a premium and Dalit gets discounted. In societal matters, it varies with the scale of economic prosperity; the upper layer facing lesser of prejudice and the bottom ones more. Many inter caste marriages have happened; typically well placed Dalit boys marrying upper caste girls (scarcely vice versa) but it has not necessarily led to social assimilation.

The caste in rural areas operates at varied intensity, from mere prejudice to crudest form. In normal course, the village community appears tranquil, really reflecting friendly relations. The tranquility lasts until Dalits abide by their space and do not intrude upon others as ordained by tradition. The moment they question this understanding, the problem starts.

How do the constructs Caste & Class interact? Is it possible to successfully integrate Caste into Class?

This duality of caste and class frankly amuses me. It is all right to speak and distinguish them at theoretical or conceptual level but not so when one is looking at a society from the perspective of bringing about change. If one uses class in Marxian sense then one has to mind that classes are defined in relation to ones place in the production system. Contrary to commonplace notion classes are not economic but subsume whole hog of things. Marx did not define class as he left many other things also undefined. But Lenin confronted the problem and had to give definition. His definition says: “Classes are large groups of people differing from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated by law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organisation of labour, and, consequently, by the dimensions of the share of social wealth of which they dispose and their mode of acquiring it". To what extent does this definition apply to castes? One would find that to a large extent castes can be viewed as classes. The only problem is that classically castes are numerous and would render themselves useless if considered as classes. However, many castes can be co-located in terms of their relations to labour and means of production. And this way it is possible to subsume castes within classes. Classes eventually should enable you to see contradiction and articulate class struggle.

Figure 7: Strength in Solidarity (1917) - A cartoon

Castes are the all encompassing life-world of people and cannot be left out in class analysis. There cannot be dual categories in Marxian theory. The notion of pure classes is erroneous. Classes are to be conceived in concrete conditions. They cannot conform to theory and would have traces of other modes of production, which I termed in one of my books as hybrid mode. It is the dominant mode that would decides the major classes in contradiction. With this methodology, the classes corresponding to the dominant capitalist mode will have castes embedded within them and would warrant anti-caste struggles to be embedded within the class struggle.

How do you compare and / or contrast Casteism with Racism?

If you ask me whether race is caste purely academically, then my answer is no. As Ambedkar concluded, there is no racial difference across castes in India; all Indians belonged to same racial stock. Castes have essentially their origin in tribal identities, superimposed by hierarchical social structure which is fortified by religious ideology. Over the years they became the life-world of people. Castes, rather caste system, have evolved into a very intricate system, with cybernetic characteristics of self-organizing and self regulating, which explains their longevity. In contrast, race is essentially biological and is marked by the hereditary transmission of physical characteristics.

Figure 8: Racial diversity of Asia's peoples, from Nordisk familjebok

Race is discerned in terms of gene frequencies differing between groups in the human species. Scientific research shows that the genes responsible for the hereditary differences between humans are extremely few as compared with the vast number of genes common to all human beings regardless of the race to which they belong. As there is as much genetic variation among the members of any given race as there is between different racial groups, the concept of race is dismissed as unscientific. Races arose as a result of mutation, selection, and adaptational changes in human populations. The nature of genetic variation in human beings indicates there has been a common evolution for all races and that racial differentiation occurred relatively late in the history of Homo sapiens. Theories postulating very early emergence of racial differentiation stand scientifically refuted. Thus, there is nothing natural in both race as well as caste.

Attempts were made to classify humans since the 17^th century as an extension of classification of flora and fauna. From that they began attributing cultural and psychological values to the ‘racial’ groups and evolved theories of superiority of races. This approach, called racism, culminated in the vicious racial doctrines of Nazi Germany, and especially in anti-Semitism. Castes, originally the innocuous tribal identities while settling from the nomadic phase to settled agriculture, came to become the ranked groups based on heredity within rigid systems of social stratification when the varna system was overlain on the society. As tribal identities itself they were in huge number unlike races spread over the vast area of subcontinent. With hierarchized notion, their number swell to such an extent that any determinate ordering became impossible, giving rise to invisible contentions between castes for superiority with others in vicinity and in turn preserving the macro structure of castes. Thus there is a difference between race and caste for sure.

Casteism & Racism

But when it comes to racism and casteism, which are the systems of discriminations, the difference collapses. Both involve inequality and prejudice based on birth and descent. Both are covered under the broader social rubric of identity. Both are ascribed and hereditary identity. While racism emphasizes skin colour or some other physical feature, the casteism stresses hierarchy based on birth with supposed religious and social justification. Their practice in daily life is reflected in differential treatment, discrimination and prejudice against people who do not form part of one’s coherent and homogeneous social groups/community (race or caste). Thus, on salient parameters of practice, both the systems appear similar.

Figure 9: Promotional poster for World Conference Against Racism, 2001

The issue whether caste and race could be equated flared up during the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCAR), organised by the United Nations in Durban in 2001. Since there is no UN forum on castes, the Dalit groups collected there contended that caste discrimination also should be included in the conference. India had signed and ratified the convention in 1969 but had not yet given accession and succession. According to Article 1 of the Convention, the term ‘racial discrimination’ meant ‘any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.’

The stand of the government was that while it is committed to eliminating discrimination in all forms, it did not consider caste as part of ‘racial discrimination’. The government as well as its sponsored intellectuals claimed that ‘caste is not race’, and that ‘caste is not based on descent’. They were wrong. It was not a question of race and caste being equal, the issue was whether racism and casteism, the praxis of them, were equal or not. The answer is unequivocal yes.}

How did most political parties deal with Casteism - right from Dalit massacres (such as Khairlanji), all the way to Subtle Discrimination?

For political parties, as explained above, caste has been the staple food. No political party participating in Indian elections, which are based on the FPTP system, can ignore castes. Not even the parliamentary communist parties could really ignore the caste arithmetic. The caste arithmetic includes all kind of dynamics depending on the situation. It includes promoting consolidation of castes as well as splitting them; it may be supporting castes and also opposing them.

Caste atrocities provide them great opportunity to show concern for the Dalits. All political parties rush to mark their presence. But thereafter the pure politics starts. As I explained in my book on Khairlanji, the main perpetrators of atrocity had a backing of BJP and NCP politicians. At the ground level the contradiction between the ruling class parties vanish and in contrast, it surfaces among the ruled ones, especially dalit parties. Both the BJP and NCP had varied influence over the state functionaries connected with the incident. They ensured initially that the incident is suppressed. Then they coloured it to show as though it was an affair of illicit relationship, suppressing the caste of the victims. Then they projected it to be the case of moral outrage of innocent villagers against the defiance of a woman that unfortunately culminated in killings of her and children.

When the public agitation exposed the incident, and forced the investigation, the parties managed to take out the main culprits and get the dummies in. During the trial, it was ensured that the /Atyachar Samiti/’s proposal for nominating their public prosecutor was not accepted and one of their poster boys, Ujwal Nikam, was nominated as public prosecutor. They drove the trial to produce a ‘design judgement’ to assuage the public opinion but simultaneously ensured that the case is weakened. The judgement firstly denied that the case had a caste dimension, there was any assault on modest of women and even a criminal conspiracy behind the crime. It is even known to school boy that the incident was a caste atrocity; it could be clearly discerned from history of past clashes that caste prejudice against the Bhotmanges was the main reason. The naked women’s bodies found out by people had bruise marks all over and injuries to their genitals, which proved that they were sexually assaulted. And, the criminal conspiracy was writ large all over since the incident of beating of Siddharth Gajbhiye took place.

Having denied all the substantial grounds of the case, the court had awarded six people with death penalty and two with life imprisonment. Any sensible person could understand that after painting the incident like a road accident, the death penalty was unwarranted. It would not stand in the higher court when it goes there for validation. But the Dalit party celebrated it. Expectedly the High Court did exactly that, commuted deaths to life imprisonment.

Figure 10: Mumbai High Court

Dalit politicians see the atrocities as their opportunity to bargain out with the ruling class political parties. Dalits look forward to them for support but they strike deals and betray them. This is not the lone incident, in most cases of caste atrocities, this dynamics can be noted in varying degree. So, all political parties including those of Dalits prey upon the caste atrocities like vultures to maximize their gains. It is not a moral problem but a systemic one. The electoral system that we adopted for our politics promotes this behaviors.}

What has been the role of mainstream media in the same?

Mainstream media’s role is determined by its objective of profitability; outlook, which it inherits from the larger society; and limitations of the people coming from upper caste/class backgrounds. There is a little difference along these dimensions between the vernacular and English media. The electronic media because of its format and reach, turns out to be worse. The overall role they play shows gross apathy, lack of empathy, and often times discriminative treatment of caste issues.

Figure 11: Delhi, February 23, 2016: Thousands marched in a rally demanding justice for Rohith Vemula

Nearly 45,000 caste atrocities take place in the country as per the NCRB, which compiles the data coming from police records. Now anyone who has little knowledge of caste operation in villages can see the degree of understament embedded in these statistics. Scholars opine that they be scaled up by a factor of 10 to 100 for a realistic picture. The bare figure itself should be shocking enough but we scarcely see their reflection beyond the local media. When an incident of rape and killing of a Delhi middle class girl took place, the media had run a campaign over several days and brought about massive turnout of people in support of ‘Nirbhaya’. But as this campaign was on, there were at least three similar cases of rape and killing took place on Dalit girls in vicinity of Delhi but they went totally unnoticed. Such bias is pervasive in media.

In the context of Khairlanji, the indifference and bias of media was exposed by some journalists themselves. A senior journalist - Rakshit Sonawane - had admitted that there was no serious media reportage on Khairlanji for about a month. Political parties and the media woke up to the Khairlanji massacre only when the agitation broke out in Vidarbha. The Delhi based electronic media, which had carried out a tenacious campaign in respect of Jessica Lal Murder and Priyadarshani Mattoo case, and catalysed a powerful movement of protest against the corrupt Police force and forced the Delhi police to reopen the case and send the accused to jail, did nothing about Khairlanji beyond some news channels customarily flashing the news in its bottom bar. Shahrukh khan’s 40th birthday was more important to it than this, one of the most horrific incidents ever. The television channels woke up only when shaken out of their slumber by the agitating Dalits. For quite some time the coverage was shoddy and sans passion that was seen in the above mentioned campaigns.

A content analysis of their programme could easily reveal ‘the underlying social perceptions and political motives around the issue of atrocities’. Yogesh Pawar of NDTV had confirmed that the initial response of television was to treat it like a crime story. It was only when he spoke to other Dalits in the village that he got a sense of the true story. While the story moved from being a crime story to be a law and order story, it was still not treated as a story of caste atrocity.

Why do media ignore Caste/Dalit issues?

Apart from the prejudice media people share with the larger society, there are other reasons too. The media is concerned with their readership/TRP (television rating points) that brings them advertising revenue. Gone are the days when media was considered as missionary activity. Even when they became corporate long back and was concerned as business, there was an element of moral responsibility displayed by them from a long term perspective. They did know that their long term profitability was hinged onto credibility which they could not afford to damage.

Figure 12: Indian newspapers for sale at a vendor's shop in New Delhi

But in the neoliberal era, which almost killed the long term, and brought in ‘here and now’ approach to things, the media ceased to bother what is not instantly profitable. They would therefore go after sensation and care for what appeals to their reader/viewer segment. Who is interested in caste/Dalit issue? Dalits are largely low educated or may not even have television to watch. So they could be ignored. Caste issues could be shown but when it has aspects of interests to others. For instance, reservation evokes general interest and hence often gets written on or discussed. With the advent of some Dalit channels and Dalit papers, of late the mainstream media perhaps realized that there is a significant numbers of Dalits who are educated and who have television and increased their dose of Dalit news. But the general prejudice against Dalits still dampen their coverage and quality of content.}

In your view, what are the biggest hurdles in annihilating the caste system?

The biggest hurdle in annihilation of caste is the political system that we have. As explained above, the castes were considerably weakened under the onslaught of capitalist relations. As a matter of fact left to themselves they could have further weakened and eventually rendered themselves irrelevant. But paradoxically, taking shelter under the Dalit argument, they were consecrated into the constitution with an alibi to institute social justice measures. As explained earlier, it was not an innocent act but an act with full design. The reservation is an exception to the general principle of equality and should be sparingly and diligently designed. It needs to be designed so as to act against the circumstances that warranted it. From this perspective if one looked at reservations that are in vogue, the colonial institution of them in favour of the Dalits appears fulfilling at least the first condition.

There could not be an argument that the Dalits who were socially excluded for centuries did not qualify to be an exceptional people to warrant exceptional policy measure. As a matter of fact, it was accepted by the larger society. The second condition warrants formulation of policy in such a way that it would hit at the root of the problem. This formulation was obvious but never paid attention to. If the reservations were projected as an antidote for the disability of the society to treat its own members with equity, the society would be motivated to overcome it and end the reservation. But it is made out that the Dalits were backward and needed a helping hand of the state for coming up to the normal level. It naturally provokes adverse reactions that why should the society of ‘meritorious persons’ be made to subsidize or support the ‘unmeritorious’ ones. Worse, it endorses the age-old prejudices that the Dalits are inherently backward. The reservations in this form also appear perpetual because of its premise as well as absence of any statement on its terminability.

Figure 13: Prof. Teltumbde after speaking at an event organized by Ambedkar Periyar Study Circle, IIT Madras (2015)

But whatever positive attributes this colonial policy possessed were mutilated and reservations were surreptitiously forged into a weapon in the hands of the ruling classes. They firstly violated the exceptional principle and extended it to the tribals. It is not my argument that the tribals were not the excluded people or were not prejudiced against, although they are not a part of the caste system. If they needed to be extended these reservations, the existing schedule could have been expanded to include them. It would have dampened the stigma associated with the schedule for Dalits. It was easily doable but this was not done.

The design behind all these intrigues was to keep castes alive. The British had created a separate schedule for the Dalits and left behind their association with the Hindu caste system. If the ruling classes wanted, the castes also could have been outlawed. The outlawing of untouchability then would have been redundant. But all this was not done. Not only reservation principle was diluted, it was made open ended by incorporating an article in the constitution which would provide for the state (read politicians) to identify such classes (read castes) which were socially and educationally backward. We have discussed this part already.

What needs to be understood is that reservations can never substitute the basic policy of empowerment of people in terms of health care, education, and security of livelihood. In absence of such a policy in place, they will always remain a tool in the hands of the ruling classes to manipulate masses.

Thus, the castes were consecrated into the constitution. It may not be wrong to say that much of the castes that we suffer today are the constitutional castes. It is an unfortunate paradox that the constitution, because of its association with Babasaheb Ambedkar as its chief architect, which was supposed to be the benefactor of the Dalits, has been their bane. The constitutional schema to preserve castes and religion and adoption of the FPTP election systems are the biggest hurdles in the path of annihilation of castes. The entire schema only produces and reproduces identity politics and identity movements which strengthen castes instead of weakening them.

Can you give us some examples of initiatives that have reduced the menace of casteism?

I do not think I have any examples to cite. However, it is my observation that the radical movements that mobilize all castes towards some goal dampen the consciousness of castes. I may cite Ambedkar’s own experiment during 1930s when he had launched the agitation against Khoti (a system of zamindari in Konkan region of Maharashtra) mobilizing tenants of all castes, Dalits and Kunabis, as an example.

His experiment during the decade when he formed his first party, the Independent Labour Party (ILP), describing it as the party of working class and he as the workers’ leader, had shown promise. But later developments forced him to return to the caste politics. It can be verily seen that the Scheduled Caste Federation that succeeded the ILP did not get him much fruit.

Whenever caste identities are dampened and the class unity is emphasized, it automatically dampened castes. Once caste is invoked, even innocuously, it tends to split anything. Caste is an identity unlike any; it only tends to split like amoeba. The inference is clear that the viable project of annihilation of castes could only be through the movement based on class unity of people.

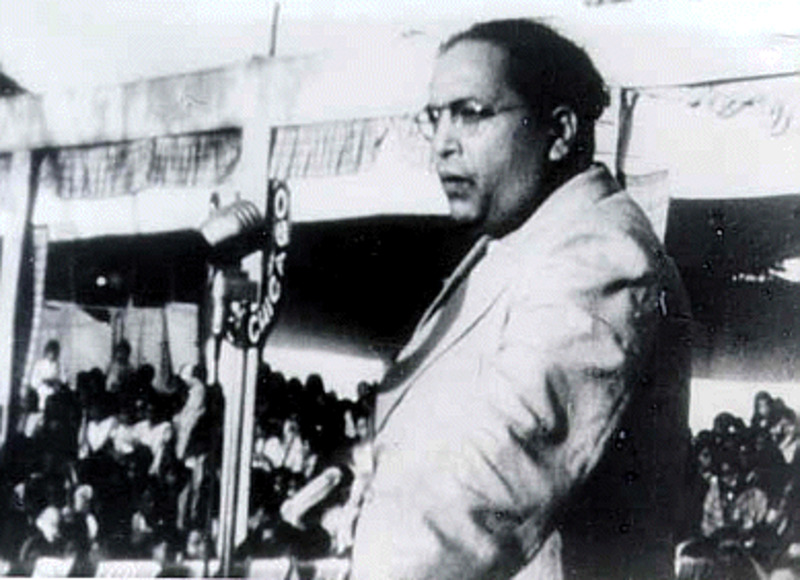

Figure 14: Dr. B. R. Ambedkar addressing a rally in Nasik, Maharashtra on October 13, 1935

Image Credits

A school for untouchables near Bangalore (March 1935) -- by Lady Ottoline Morrell, released into the public domain

A banner outside the 2012 Republican National Convention in the USA depicts one of the quotes of Martin Luther King, Jr -- by Liz Mc, released under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

Inauguration ceremony of Kilvenmani martyr's memorial in Nagapattinam (2014) -- by Jaffar Theekkathir, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license

VP Singh, Prime Minister of India (1990) -- by Rsamy2008, released under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal license

Strength in Solidarity (1917) - A cartoon -- by Ralph Chaplin, released into the public domain

Racial diversity of Asia's peoples, from Nordisk familjebok -- by G. Mutzel, released into the public domain

Promotional poster for World Conference Against Racism, 2001 -- by United Nations Department of Public Information, released into the public domain

Mumbai High Court -- by Sualeh Fatehi, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5 Generic license

Indian newspapers for sale at a vendor's shop in New Delhi -- by Shajankumar, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license